“The snake alerts me to negative energy; but he seems to like you,” he chuckled as he prepared our shots of Sodabi. He handed me a cup, then took the snake from around my neck and placed it gently back around his.

“Vodun is very powerful, but it is neither good nor bad. It has no intention. It is like a knife, or a spear. It sits still, without emotion. It is you who stabs the knife or throws the spear, who determines its energy.”

The concept of using Vodun as a weapon captivated me. I encouraged him to elaborate. He spoke of an ancient system of justice that predates the legal systems of the modern world.

“Vodun may be used for justice, yes. If another man kills your wife, what do you do? Revenge by your hand would continue in a cycle of violence, so instead, you may pray to Heaviosso, the Vodun sky god and purveyor of justice. Perhaps he strikes down your enemy in a rage of thunder and lightning.”

In a land which has historically lacked the luxuries of an effective criminal justice system, I could understand the practicality of Vodun justice.

“But you must understand, Vodun is not a toy. You must use wisdom. You must have responsibility. You could hurt yourself and hurt others. Just like the blade of a sword, it is sharp, do not play with it like a toy.”

The more he spoke of Vodun, the more he appeared like a Jedi master elucidating on The Force from Star Wars.

“You want to make this girl fall in love with you, Vodun will make it happen. You want to heal this sickness, Vodun will make it happen. You want to grow crops for food, Vodun will make it happen. Whatever you want, the Vodun spirit will give… But you must first ask… And you must use Vodun for positivity only. If you use Vodun for negativity, in a bad way, it will come back to you.”

Glele put the snake back around my neck as I contemplated his words. The snake snuggled up in a comfortable position, and he proceeded with an unexpected question for me.

“So… what is it that you want from Vodun?”

I momentarily went blank, sensing the weight of karma and personal responsibility on my conscious similar to the way the snake had coiled itself around my neck.

“I want to understand… To be able to see the world the way you do, through the eyes of a Vodounon.”

He paused for a moment, silently reflecting on his thoughts, looking at the snake wrapped around my neck. He rolled the cowry shells, mumbled something in an unfamiliar language, then turned back toward me.

“Okay my friend. Vodun shall reveal itself to you.”

Egou (at a Vodun festival)

I took a break from Ouidah for a few days while Odjo returned to his business and family. In the meantime, I explored the side streets of Benin’s coastal highway when Tessi and I first crossed paths. He wore a collared orange and black shirt with shorts and sandals, striding with a hop to his step like he was jamming to a song playing inside his head. He spoke five different languages, including English, much to my delight and conveyed an infectious friendliness about him that was rare in Benin.

He took an interest in my Vodun curiosity upon our introduction, and he offered to help me along my journey simply for the sake of helping.

Tessi was an old soul in a young man’s body. He liked to sit back with one foot resting over his knee, with a habit of extended pauses of contemplation before jolting upright with vigor as his stream of consciousness flowed into spoken words.

Born of a Christian mother and Vodun father, Tessi was considered a Christian at birth. His original name was David. At the age of four, he fell seriously ill, falling into a coma for multiple days before being pronounced dead.

It was at that moment that his aunt, a Vodun priestess, called on the spirit of his deceased grandfather to help bring him back to life. As the story goes, his grandfather reincarnated into David’s body, helping maintain his lifeforce, while his body began to heal. David miraculously survived with a full memory of the ordeal. Later, he formally converted to Vodun, choosing to be called Tessi as his native African name.

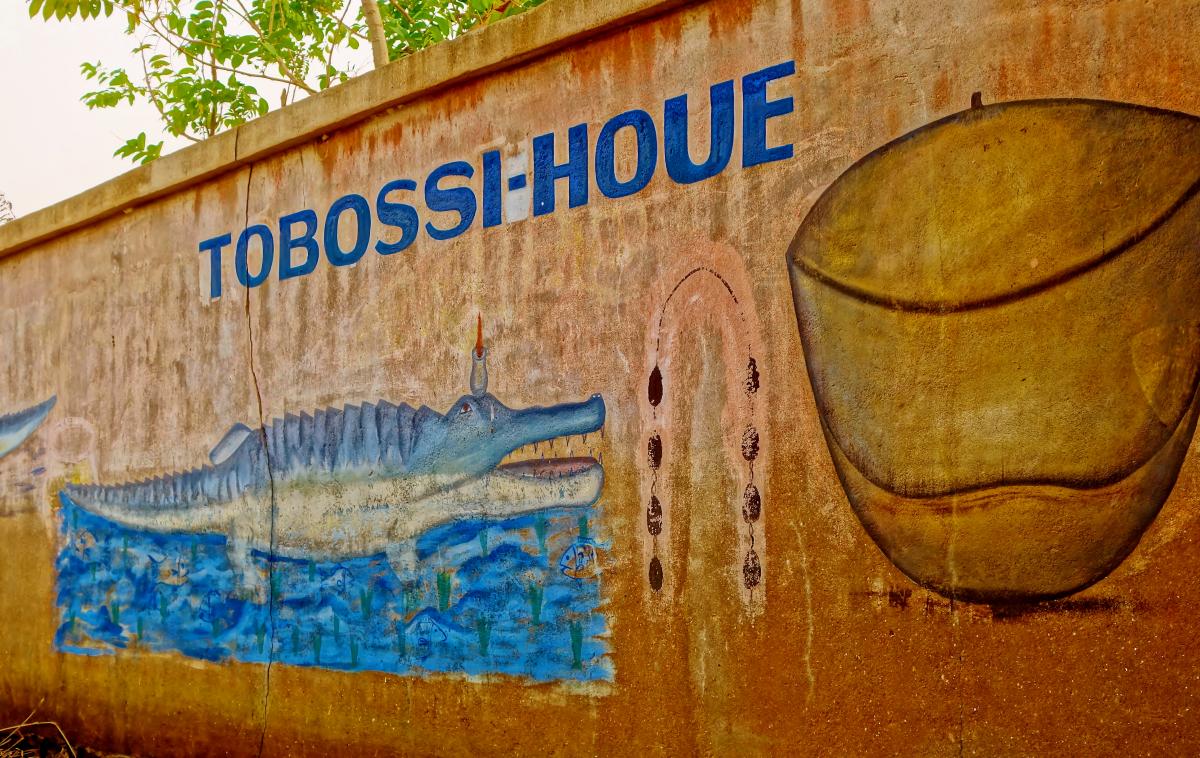

Tessi sitting next to a fetiche

His home had individual rooms for fetiches dedicated to Egou, the warrior god of metals and craftsmanship; Dan, the rainbow-colored snake god, who also served as the patron deity of his grandfather; and Sakpata, the god of the earth with associations to health and wellness.

Tessi’s concept of Vodun was holistic and harmonious.

“We are all connected. We call it the spirit of Africa; the spirit of Vodun, which is the connection. The earth, nature, the living beings, the spirit world; everything is connected. This is Vodun.”

His convictions were strong, and his energetic sense of spirit overflowed as he spoke. In his eyes, there was a sense of meaning to the occurrences of everyday life.

“Everything happens for a reason. It is the way of Vodun. That is why our individual character is so important. How we handle adversity and opportunity; they happen for a reason, and we must embrace the path presented to us. Like when I first met you wandering alone on that street… You may have appeared lost, but no, I knew that you were there for a reason. We are connected, you see…”

I had to give him credit; in a land where corruption is rampant, opportunities are scarce and trust is rare, Tessi was overflowing with enthusiasm and integrity.

But I needed more clarification on the nature of Vodun. Was it an abstract natural force, or did it have a deeper meaning? What was the underlying point of it all?

“My brother, think of it this way… what is the point of music? What is the point of dancing? You see, we are all connected, like the individual notes in the symphony of life. We are all one. So, my brother, go make beautiful music. Everyone that crosses your path is a musical note in the song that is life. Everyone and everything, the plants and animals, the earth, we all must create the melodies to make life on earth like beautiful music. That, my brother, is Vodun.”

Tessi had been born in a hut in a small African village, yet he possessed the wisdom of a thousand lifetimes. He called it “L’espirit d’afrique.” If he does not one day end up as a leader of his country, the world will be a lesser place for it.

Tessi agreed to take me to a rural African market farther inland and far off the beaten path. We ventured out on his motorbike, following the bumpy dirt roads, which diverged into narrowing footpaths, to a primeval part of the world trapped in an ancient way of life.

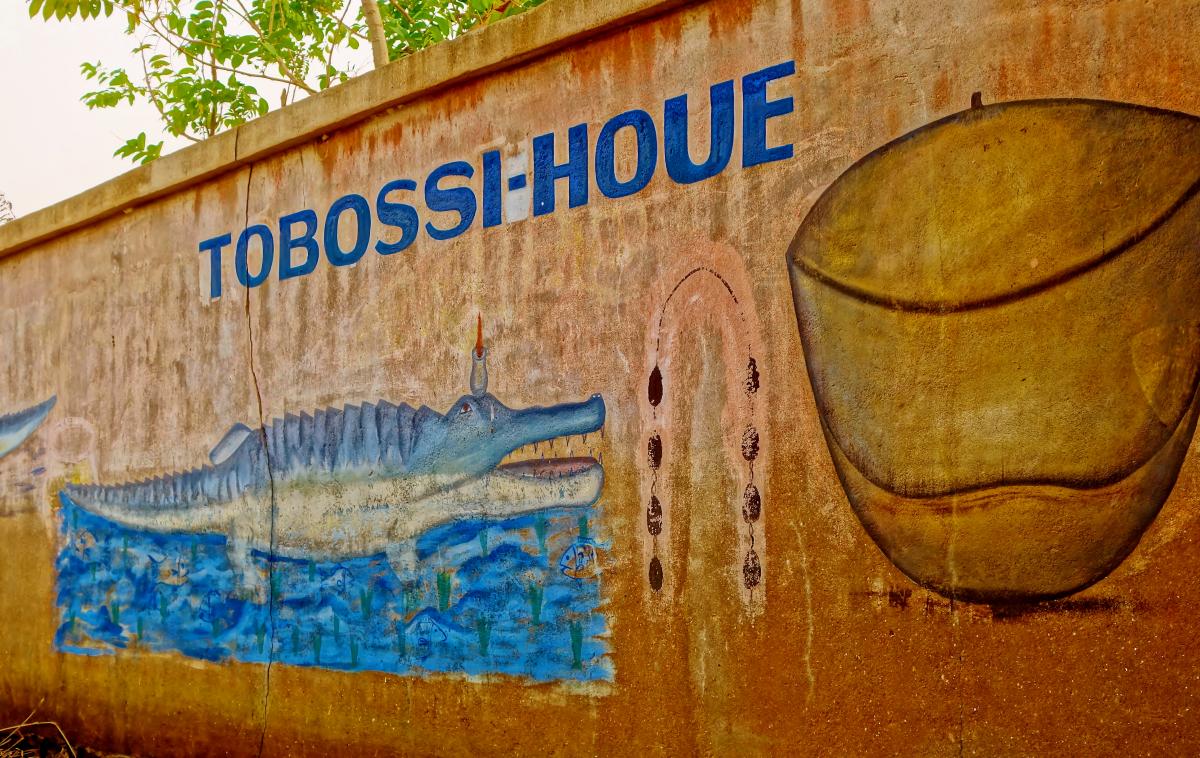

The cinderblock walls were decorated with images of an obscure crocodile god; the lone doorway was guarded by a white sheet of linen dancing against the breeze. Otherworldly chanting could be heard from within the the roofless structure. We parked the bike and began to explore, forgetting about the market at which we would never arrive.

Tessi clapped his hands twice, upon which an elderly woman draped in a royal blue shawl appeared at the doorway. Other individuals in similar garb looked on from behind her, fixated on the unusual foreigner, who was clearly in a time and place that he did not belong.

It was an unparalleled moment of serendipity; we had accidentally wandered into a ceremonial gathering of priests and priestesses partaking in a sacred ritual in a rural tobossi-houe- otherwise known as a Vodun “trance house.”

Tessi negotiated our entrance based on his Vodun connections, but not before I rid myself of my western attire and draped a white linen around my waist in a similar fashion to the others. They wore robes of white and royal blue with matching beaded necklaces. Silent feet bearing scars from a lifetime of shoeless labor poked out from under the robes.

The tobossi-houe was dedicated to the spirit of a locally venerated crocodile deity (whose name I never knew). The chief Vodounon was identifiable by his flawless white tunic and a matching cap. He went by the name of Azangli. His presence was commanding, as he stood in silence with a penetrating, unshakable glare.

Azangli lifted his arm in our direction pointing his finger at the ground. It was a signal for Tessi and I to kneel before entering. A woman knelt alongside us and rolled the cowry shells while she spoke to the spirit world. She tapped my shoulder to observe; the cowry shells indicated a positive sign from the Vodun gods. Azangli gave us a dubious nod, allowing us to proceed.

The outer room hosted two life-sized crocodile figures, each dyed green with their jaws stretched open wide. The heads of the crocodiles were freshly covered in blood, remnants of a goat sacrifice from earlier that day. A wooden throne, shaped in the traditional design of the Dahomey kings, sat between them.

Azangli had moved behind the entrance to the inner room, his piercing eyes tracing each of our steps with an apprehensive glare.

Azangli

The inner room was a sacred chamber featuring a stunning Vodun fetiche unlike anything I had ever seen. A large rectangular altar was positioned in the middle of the room, roughly three feet high and maybe twice as wide. Layers of the skulls, skins, carved wooden objects, ornamented figures, offerings and other fetiche objects sloped like pyramid walls from its sides. Offerings of palm oil and bottles of gin lay close by. Atop the altar sat six crocodile heads; three life-sized carvings crafted from single blocks of wood, alongside three genuine crocodile skulls. Each of the crocodile jaws was open, with a large egg the size of a fist placed neatly at the end of its snout, between the upper and lower front two teeth.

This was the rural community’s holiest of holy sites, their sacred Vodun cathedral, and we had unintentionally interrupted a moment of ritual worship that my eyes were never meant to have seen.

Azangli pointed to the ground with the commanding presence of an emperor, and we quickly kneeled along with the other dozen or so Vodounons in front of the altar of crocodile skulls. He recited a prayer while our foreheads kissed the ground. The rest of the group remained silent.

A silver-haired woman wearing only a blue shawl around her waist handed me the bottle of sodabi. She moved about with the aging grace of royalty, appearing to be the high priestess of the sect; the spiritual queen to Azangli’s king. Tessi and I each took two sips, the first for ourselves, and the second to be spit out directly at the foot of the skulls.

She knelt before the altar and rolled the cowry shells to determine the fate of our visit. Azangli sat on his throne in silence while he anticipated the message of the gods.

She gave him a nod while she recited a prayer of gratitude in the Fon language. He returned the nod in our direction, speaking directly to us for the first time.

“You have no negative energy, and the Vodun spirits have welcomed you,” he said in a sonorous voice that echoed with a charismatic gravitas fit for a king.

I was overcome with a mix of euphoria and relief. I looked back at Tessi to see his face lit up with a confident “I told you so” shine in his eye.

“What is it that you want?” Azangli continued. “Answer me, and we shall pray together.”

Azangli’s question was literal, and he expected a precise answer. The Vodounons stared back at me in silent curiosity as soldiers of Azangli’s spiritual realm.

For a moment in time, all energies possessed by the Vodounons in the tobossi-house would be focused on the subject of my request. That my wish would be granted was taken as an absolute certainty.

It was the law of attraction; ask and you shall receive. Azangli sensed my ignorance, switching roles from monarchical sorcerer to Jedi philosopher; he was the human incarnate of Yoda crossed with Professor X.

“If you want money, you will receive it, but you must help others who are poor. If you want food, you will receive it, but you must feed others who are hungry. If you want health, you will obtain it, but you must help others who are suffering. You must return to Benin to pay your respects, so you can share the blessings with the Vodun spirits.”

Vodun manifests itself like esoteric magnetism; it rewards humility and punishes hubris. Pay it forward, show gratitude, and the positive energies of Vodun would guide me to prosperity. Act selfishly or wish harm to others, and I would be punished to the identical degree.

The Vodounons circled around the room and knelt before Azangli, their hands held together solidifying an impenetrable ring around the altar. I knelt alone at the foot of the crocodile skulls with Azangli directly to my side. He sat on his throne and bellowed a prayer to the spirit world while the high priestess showered the crocodile altar with offerings of gin and palm oil.

The Vodounons were synchronized in rhythmic chanting in between deliberate pauses from Azangli. I kept my eyes tightly shut with my forehead buried in the dirt floor, internally balancing the flooding sensations of gratitude and awe. I tried to breath slowly and soak in vitality of the moment. Time and space stood still as my ego momentarily vanished, only to return instantaneously with the unmistakable feeling of deja vu.

I raised my head to wipe the dirt from my face. The high priestess handed me a communal cup of sodabi, formally ending the ceremony. Azangli granted me a silent nod of approval while I stood on my knees, eye to eye with the jaws of a crocodile skull. I was offered a bowl of cassava and goat innards, and I politely chomped away at the rubbery flesh. Azangli appreciated my efforts, finally cracking a smile.

He offered me a single photo upon my exit, a solo portrait of himself on his throne. Then Tessi and I began our slow journey back towards the modern world.

Odjo had been awaiting my return to Ouidah. He had arranged for me to meet a highly revered Vodounon, assuring me that all of my questions about Vodun would be answered.

Zomadonou’s home was located down a dirt road extending inland from the outskirts of town. He was tall with a sinewy frame and gumby-like arms and legs, topped by a white cap similar to a Muslim taqiyah. He moved about with bolts of energy from the base of his spine, constantly veering in roundabout directions as his attention shuffled between thoughts like a mad scientist.

He welcomed Odjo and I with a toothy smile and a handful of cowry shells; a few rolls of the shells eliminated any further hesitations: Odjo and I were meant to be there.

“The power of Vodun is like the power of the sun,” he spoke with his palms open and arms spread outward, strategically tweaking his voice to emphasize his points.

“Just as the sun gives energy to life on earth, Vodun gives life to energy on earth. It is the connection of life and energy, the duality.”

I asked about the similarity to Yin and Yang, but was met with a blank stare. The abstract philosophy was enchanting, but I wanted to understand its practical application.

“All living things consist of energy; this energy comes from the same source. Like sun rays that come from the sun; separate, but at their essence, the same. Vodun is like the sun, and we are the light… So, we must shine.”

This prehistoric animistic religion sounded remarkably like new age philosophy. I began to wonder if humanity’s approach to spirituality may be coming full circle from the time of the ancients.

I wanted to know more. Could an outsider like myself harness the powers of Vodun?

“Vodun… You cannot touch it… Like light, it has no shape…” His hands maneuvered through the air as if he were sculpting his thoughts from an unseen block of clay.

“It begins with the state of your mind. Your mind creates your thoughts. Your thoughts become your behaviors. Your behaviors create the state of life on earth. So, the state of earth is a reflection of your mind. When the earth is suffering, it is a reflection of the mind of the people.”

The emphasis on the connection with the energies of the universe was evident, the role of positivity undeniable. But, the stigma of malicious evil spirits remained. The ritual scarification only seemed to intensify this fear, and I could not understand its practicality. I began to point to the scars and ask, but Zomadonou remained one step ahead.

“You do not understand the forces of evil spirits, because you cannot see them. The Vodun scars help us to see them; they know that we are watching. We defeat them with our mind.”

I had ventured too far into the deep end, and was no longer able to keep up. My face must have reflected my confusion, as Zomadonou sensed my optimistic curiosity beginning to sour. He slyly turned his attention to a handful of cowry shells. Lighting a candle while he had a word with the spirits, he rolled the shells two times, then looked back at me.

“I can cleanse you of the evil spirits, if you want, but first, you must ask for it yourself. Your Vodun power will be revealed to you.”

I wasn’t sure exactly what that meant… But how could I say no?

I looked at Odjo, who gave me a nod; I returned the nod to Zomadonou.

“We will have a Vodun ceremony for you. To cleanse you of negative energy and evil spirits. The Vodun spirits give you protection, show you Vodun powers, now and in the future.”

I could feel the universe laughing at me once again. I had wanted to learn about Vodun from the perspective of its most spiritual adherents, and here I was, in the back alleys of Ouidah, with the opportunity to have a powerful Vodun priest perform a ritual ceremony to conquer evil energy and reveal the Vodun powers of my own inner spirit.

I was ready to go all the way.

I wore a white linen cloth over my teal Beninese trousers, no shoes or shirts allowed. The outdoor courtyard behind Zomadonou’s home featured conglomeration of peculiar fetiches laid out on a mat. The fetiches were covered in a messy blend of dust and dried blood. Their specific purpose remained unknown.

Zomadonou and I kneeled in front of the fetiche while he rolled the cowry shells and recited a prayer. Odjo and other locals had gathered around us as spectators, their eyes dancing with fervor at the site of a foreigner, who they began referring to as their brother.

A young girl handed Zomadonou two live chickens.

He held the chickens upside down, as if their legs were handles. A groundswell of fear consumed me once again; suddenly I knew what was coming. I had yet to witness ritual sacrifice as part of a Vodun ceremony, and I had never ever expected to be an active participant. The feeling was unnerving, but I had to respect the cultural norms; I was a guest in his home, and they were not my rules to reform. I looked into the chicken’s eyes and apologized from within.

Zomadonou traced the chickens over my body like a metal detecting wand, reciting a prayer in the Fon language throughout the process. Using a sanctified knife designated strictly for ritual sacrifice, he cut their throats one at a time and dripped the blood over the fetiche in absolute silence.

It is during these moments that the Vodun spirits manifest on earth, deriving strength from the blood of the sacrifice, and performing the divine miracles of Vodun lore.

In my case, that meant a spiritual cleanse of evil and negative energy, with the hope that my so-called Vodun powers would become actualized. Zomadonou again began to speak aloud to the spirits, while the chickens ceased to suffer no more.

The next step was a purification bath. Across the courtyard was a barrel filled with sanctified water and freshly gathered plants, whose mixture had been specifically formulated for my individual ceremony. I was instructed to drench myself completely in holy water using the vines that had been soaked inside the barrel. It was a cleansing in the most literal sense, and I was given my privacy behind a white curtain hanging from clothesline in the courtyard.

I returned to the fetiche mat and slowly took a seat on a stool placed near a circle drawn from flammable black powder. Zomadonou crouched next to me and placed a cup of dark powder on the ground.

He opened the palm of his hand to reveal an unopened razor. Zomadonou slowly unwrapped the razor’s packaging while giving me a nod. My jaw clenched to a petrified state. My voice failed me as my hand defensively shielded my face.

Ritual scarification on my face was a line I would not cross.

Zomadonou laughed at the weight of my trepidation and turned his attention to the village children, who looked on as eager spectators just a few yards away.

“We no longer cut our faces; look at the children.” He said in a confident tone.

It was an observation that I had missed entirely. The faces of the children were clear and unblemished.

“Now we make the cuts very small… around the body,” he said as he waved his hand in a circular motion to my chest and shoulders.

I stared at the razor blade as my heart began to beat with the intensity of an African bongo drum. I took a deep breath and accepted the unknown outcome of my fate… there would be no going back.

He cut me twelve times; six pairs of small incisions on both shoulders, both sides of my torso, my chest and my back. The small slash marks were painless, the trails of blood were minimal.

Zomadonou quickly rubbed the chalky mixture of soot-like powder deep into the open wounds, chanting to the gods. The powder instantly transformed the cuts into tattoos, solidifying their permanence and enhancing the visceral effects of scarification.

I felt no pain.

The cleansing ceremony with Zomadonou

We broke from the formality of the festivities to share an evening meal with the local community. The growing darkness of night consumed Ouidah as we broke bread together.

We returned to the outdoor courtyard and immediately consulted with the spirits. Situated before us was a fetiche-sack crowned with the heart of a chicken and soaked in scented oils and sacrificial blood.

I positioned myself directly inside the flammable black circle while Zomadonou called out to Sogbho, a potent sky god of the Vodun pantheon associated with the power of explosives. I cradled the fetiche-sack in my hand and balanced the chicken heart on the surface. I extended my arm outward toward the stars.

Zomadonou put a match to the base of the circle, its outer edge igniting in both directions. He shouted at the nighttime sky as I held the fetiche steady with the focus of a sniper.

The onlookers were spellbound by the blazing circle of firecracker powder and booming Vodun oratory. Zomadonou’s arms thrashed through the smoke and shadows like an inflatable tubular air dancer, enhancing his grandiloquence in a cinematic fashion.

The fire burned out as Zomadonou’s words tapered off. The fetiche remained steady; the heart did not fall. The audience roared with approval. Zomadonou confirmed that Sogbho triumphantly cleansed all negative energies and evil spirits from within me.

He took the fetiche from my hand and led me into a shadowy crypt-like chamber at the far end of the courtyard for one final task.

He lit the chamber with scented candles, illuminating the carved wooden figures of Vodun gods and the sacrificial offerings of past ceremonies. We knelt before a small altar positioned against the center of the far wall.

Zomadonou tactically moved the candles and fetiches along the edge alter. He rolled the cowry shells, crooning with the spirits one last time. He handed me a cup filled with dark powder, mixed it with soda, and instructed me to drink it all.

I had never come across any information regarding this type of ritual during my pre-trip research, and thoughts of its potentially harmful effects swirled through my head with the uprooting force of a tornado.

When I asked what it was, the only answer I could get was “Vodun drink… so the Vodun stays with you.” Hey pointed to his gut before extending his finger in a circular wave around his body.

I wrapped both hands around the cup, held it to my lips and contemplated my fate. This was uncharted territory.

The Holy Grail scene from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade flashed in my mind; his quest for knowledge of the divine had taken him through the depths of legends, until he held the cup of Christ in the palms of his hands.

The stakes were a far cry from the fate of mankind, but nevertheless my moment had come. I had asked for knowledge of Vodun, and the final challenge now similarly rested within my own two hands. The allure of this ancient knowledge was irresistible.

I took a deep breath as I took one last look around the room, the shadows of Zomadonou and the fetiche statues waving in the flickering candlelight of the crypt-like room. I shut my eyes, tilted the bottom of the cup to the pitch black ceiling, and let the Vodun drink flow deep inside of me until every last drop was gone.

It was surprisingly smooth, and it tasted like candy. I gradually opened my eyes, letting it all settle, slowly breathing in the tranquil fragrance of the scented candles.

I felt great.

I looked around the room, momentarily fixated on the reflections of light dancing against the scars and the smile adorning Zomadonou’s face. My own smile reflected his, and we started to laugh alongside each other.

My hands no longer trembled. The muscles around my neck loosened up. The tightness in my back relaxed.

The fear that had consumed me since that first moment in Ouidah began to melt away, until it evaporated completely. I was quickly seduced by a feeling of illumination, swept up in a profound moment of clarity.

The concept of evil was symbolic; the evil spirits had been a metaphor for fear.

The scarification served as an esoteric vaccination against the malaise of fear. The ring of fire signified its metaphysical crematorium, incinerating the clutches of fear in a grandiose public execution. The ritual cleansing was a metaphorical polishing of our inner shine.

It all clicked.

Fear, particularly fear of “the other,” has divided humanity since the beginning. Fear prevents us from connecting. The evil spirits that have plagued the unity of the human race were never an external force to be battled with swords and superstitions; they were a force from within, an individual blemish on the universal consciousness of the human spirit.

United we stand. Divided we fall. It all became perfectly clear.

Zomadonou’s sacred chamber turned to complete darkness as he blew the candles out, but only then could I finally see the light.

So, what is Vodun?

Vodun is a dazzling expression of ancient superstition and new age spirituality, which sees all life in the universe as a connected natural force.

It is Buddhist karma crossed with The Force from Star Wars; an impartial power of the Law of Attraction traveling a circular path through the cycle of life.

It is the prehistoric science of the natural world; a polytheistic system of divinity, reason, and justice; an omniscient answer to the mysteries of life.

It is the sound of music; the harmonious vibrations that flow from the rhythms of our mind.

It is the spiritual companion, the Yin to the Yang, of the life giving energy of the sun.

It is the organic energy which connects the physical and metaphysical realms, and it exists within us all. It can be influenced at will, by those keen enough to understand the nuances of its vitality; it is “the vibe.”

It is the universal divine spirit, known by many different names in many different cultures across the globe and throughout history; whatever you want to call it is ultimately up to you.

I had one final question for Zomadonou about the nature of my soul and the spirit of Vodun; I had been exposed to so much on this crusade, and I was trying to sort it all out.

“I want to know – this adventure to Africa and my whole experience with Vodun – Did I choose Vodun and create this journey myself, or did Vodun create this journey and chose to take me along for the ride?”

He sprang up from his seat in a eureka-kind of moment, put both hands on my shoulders, and flashed his omniscient grin. Looking me straight in the eye, he began to answer. I should have seen it coming.

“… Yes.”

The following day I hitched a ride down West Africa’s coastal highway, en route to Farafina’s seaside Rasta beach in Grand Popo. I wanted a place to relax and reflect on it all, and sure enough, I found an empty hammock hanging from a palm tree waiting for me on the beach. The lyrics of Bob Marley echoed from a bar in the distance…“one love, one life…” As they say in Benin, “la vie est belle.”

One of the first and most traditional ways of getting around the UK is by train, which still has a large network which will serve the vast majorities of towns and cities across the country. However, to plan a journey can be quite difficult, so using a website that will offer a journey planner as well as selling tickets can be useful, and there is also a telephone number which can be called that has access to the various networks.

One of the first and most traditional ways of getting around the UK is by train, which still has a large network which will serve the vast majorities of towns and cities across the country. However, to plan a journey can be quite difficult, so using a website that will offer a journey planner as well as selling tickets can be useful, and there is also a telephone number which can be called that has access to the various networks.

Another great city to visit in the UK is Manchester, which is not only a musical hotbed, but home to two excellent football teams competing in the prestigious Premier League. Anyone visiting can enjoy the wide range of venues which offer live music throughout the week, and then enjoy the weekend seeing some high quality football.

Another great city to visit in the UK is Manchester, which is not only a musical hotbed, but home to two excellent football teams competing in the prestigious Premier League. Anyone visiting can enjoy the wide range of venues which offer live music throughout the week, and then enjoy the weekend seeing some high quality football. When it comes to the cities across Britain, there are many which offer cosmopolitan destinations, but when it comes to history, the UK’s smallest city St David’s is exceptionally beautiful, and has a historic cathedral that is the envy of many larger cities.

When it comes to the cities across Britain, there are many which offer cosmopolitan destinations, but when it comes to history, the UK’s smallest city St David’s is exceptionally beautiful, and has a historic cathedral that is the envy of many larger cities.

The best tip in order to travel on trains for the best price is to book in advance, as this will make it much easier to know the times of the journey and to plan accordingly, and to make sure the journey can be achieved and transport to and from the station is in place if necessary.

The best tip in order to travel on trains for the best price is to book in advance, as this will make it much easier to know the times of the journey and to plan accordingly, and to make sure the journey can be achieved and transport to and from the station is in place if necessary. The train system in Britain is a great way to get around and to see the country, and there will usually be a ticket that will not only be suitable for the journey being made, but can also be bought at a competitive price when booked well in advance.

The train system in Britain is a great way to get around and to see the country, and there will usually be a ticket that will not only be suitable for the journey being made, but can also be bought at a competitive price when booked well in advance.